Initiated and supported by HCA Vanadzor, “Cultural Genocide in International Law: A Case Study of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh” report was prepared by Sarah Michie – a graduate of the University of Dundee, Scotland, UK- in the frame of Armenian Volunteer Corps project. The report is available in English.

Aim & Purpose of this Report

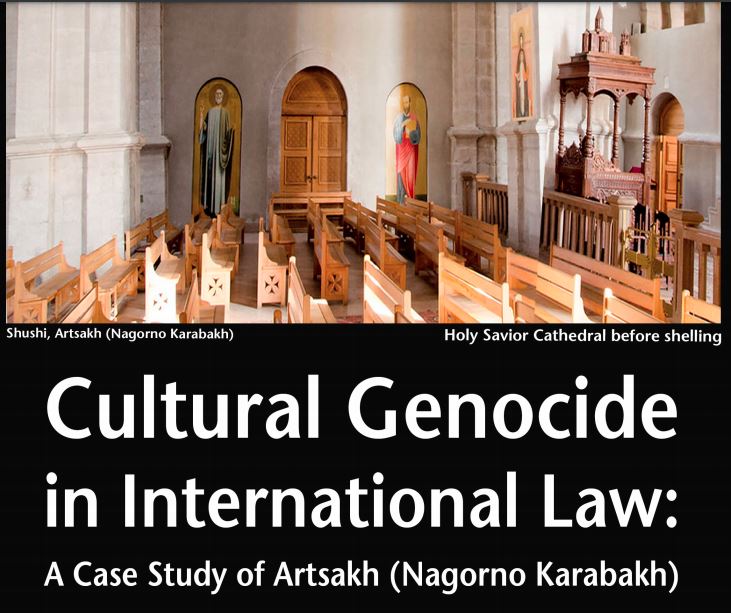

During the Nagorno Karabakh/Artsakh conflict in 2020, much of the focus was on the threat to life and the displacement of peoples. Yet in the aftermath, it became clear that not only were lives lost, but important cultural sites, buildings and monuments had been damaged or destroyed. Artefacts dating back to the 4th century had been damaged beyond repair,

churches and mosques shelled and statues toppled.

It is not uncommon for such ‘cultural cleansing’ to occur during wartime; in fact it is well recognised throughout history as being a common outcome, and has many academic papers dedicated to it. In response, international treaties and laws have developed to protect the cultural properties of all peoples, and many cases have passed through the International Criminal Court in recent years which hold perpetrators to account. It is well understood by nations throughout the world that destruction of cultural property is a crime against mankind, yet it continues to occur even now.

This report aims to understand why cultural property has been actively and deliberately destroyed during the conflict in Nagorno Karabakh, identify the scope of crimes committed against Armenian culture and consider any potential resolutions available to Artsakh. It should be noted at this stage that this report does not intend to minimise the human cost suffered in the conflicts discussed below. It is without contention that cultural property destruction almost inevitably follows armed conflict. As stated by the Chamber of the International Criminal Court in the case of The Prosecutor v Al Mahdi, ‘[i]n the view of the

Chamber, even if inherently grave, crimes against property are generally of lesser gravity

than crimes against persons.’

Cultural Genocide in International Law: A Case Study of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh)

Concluding Thoughts

This report has attempted to review both the jurisprudence and practical measures taken by the international legal community over the past 100 years to understand the importance of, and protect, cultural property. It is clear that whilst those who are signatories to the Rome Statute enjoy the protections of the United Nations and the deterrent of the International Criminal Court, those who are not signatories are expected to make a more proactive approach to protecting their own cultural property. In the case of Artsakh, this is simply not possible as Azerbaijan holds the territory and therefore Armenian agencies cannot enter the area or take proactive steps to protect sites or artefacts without being endangered or accused of nefarious activity.

On a positive note, it is extremely encouraging to see third party States step in to aid the protection and preservation of cultural property, particularly in Syria and Iraq following ISIL’s occupation. This serves to demonstrate that the protection of cultural property is an international issue and is best managed by careful cooperation between States.

Moving forward, this report concludes by calling for more formal and international-level support for states to protect cultural properties. For this, we believe that UNESCO should make every effort to visit these territories, especially those under the control of Azerbaijan, in order to compile a list of the most significant cultural sites, give an independent assessment of their condition and damage caused, and take all necessary measures to protect the Armenian cultural heritage. This will facilitate the monitoring and preservation of historically Armenian cultural heritage, and if necessary, allow UNESCO to become an intermediary in the process of returning cultural property to its country of origin where appropriate. We also suggest that the UN Special Rapporteur for Cultural Rights and other responsible bodes visit these territories immediately to prepare a report, documenting the present state of the cultural property and therefore deterring any interference by Azerbaijani authorities, or encouraging their protection from non-governmental actors who may wish harm upon them. With the correct and careful intervention by third-party actors, the destruction and abuse of cultural property can be safely mitigated without the risk of

further conflict in Artsakh.